25 May 2022 The Latvian lynx case – when successful conservation fails on bureaucracy

Healthy populations, few conflicts: Latvian lynx management delivered successful outcomes for decades based on clear conservation actions and well-regulated hunting quotas. The recent moves by Brussels will undoubtably damage this successful system, thereby increasing conflicts.

The European Commission (EC) opened a formal infringement procedure against Latvia regarding its successful Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) management, surprising many stakeholders (link). According to the EC, a strictly protected species cannot be in the same category as a huntable species and is therefore calling on Latvia to change its national laws.

Through an approved national action plan, the Latvian lynx population has remained healthy and in a “favourable conservation status”. This is not only important for Latvia but for the conservation of the Baltic lynx population in general[1]. Latvia’s action plan contains important recommendations for some restricted regulation by hunting, which can be immediately reduced if required. This plan has been highly successful, and was even recommended by the EC as a ‘best practice’ example in its previous Guidance document on strict protection (see table 1).

2007

Example: Latvian Lynx management plan

The plan was prepared by national experts and confirmed by order of the Minister of Environment and Region al Development in 2002. The entire text is available here.

The plan forms the basis for a long-term strategy for the conservation and management of the lynx in Latvia, including strictly limited harvesting of the population by hunting. It takes a long-term view, where the lynx in Latvia currently has its best distribution status within the last 150 years and is considered to have a favourable conservation status.

Limited and strictly controlled taking by hunters is considered to have a positive impact on the population as well as on public perception. The practice thus fully complies with Article 16(1)(e) of the Habitats Directive.

2022

Nature: Commission calls on LATVIA to improve its rules on species protection

The Commission calls on Latvia (INFR(2021)2260) to bring its national legislation into line with the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC), especially as regards the protection of the lynx. Article 12(1) of the Habitats Directive requires Member States to establish a strict protection regime for the animal species listed, which includes the lynx species. Derogations from the strict protection system are possible, provided that precise conditions are met. Despite a 2020 report by the State Audit Office of Latvia that recommended to bring national law in line with the Habitats Directive, the Commission considers that it is still not the case. The Commission therefore decided to send a letter of formal notice. Latvia now has two months to respond and address the shortcomings identified by the Commission. In the absence of a satisfactory response, the Commission may decide to issue a reasoned opinion.

Table 1: While in 2007 the Latvian lynx management plan was used as a best practice example in the EC´s guidance on strict protection (left), it is now in the centre of an infringement procedure (right).

Latvia forced to change its national policy

Due to the EC’s pressure, in December 2021, the Latvian government did not issue any hunting permits in order to resolve the formal matter raised by the EC. More recently, the Latvian government removed the lynx from the hunting regulations and placed it under the strictly protected species regulations. Rural stakeholders are now extremely worried about the conservation of the lynx population in Latvia. Before, the species was highly valued by hunters, who were active in monitoring and in reducing conflicts.

Call for flexibility in EU large carnivore policy

The EC is taking a stricter approach to large carnivore management in Europe. This has sparked major concerns by Europe’s largest rural stakeholders (link), arguing that this is not in the long-term interest of people and large carnivore conservation in Europe. The EC’s approach to Latvia also goes against previous Member State requests, which have asked for more flexibility in implementing the Habitats Directive (link):

“Without jeopardising the conservation objectives and requirements set within the Nature Directives, RECOGNISES that the flexibility of implementation approaches that take into account specific national circumstances contributes to the reduction and progressive elimination of unnecessary conflicts and problems between nature protection and socioeconomic activities, as well as to addressing the practical challenges resulting from the application of the annexes to the Directives (point 6, link).”

Stalemate for the lynx?

“We are at a stalemate and unfortunately the only loser will be the Latvian lynx”, said FACE President, Torbjörn Larsson, who expressed his disappointment at the European Commission: “It is frustrating to see how the European Commission is calling on Latvia to change its successful management plan, which is actively supported by the rural stakeholders and delivering conservation results at a time when Europe is failing miserably to conserve biodiversity”.

Linda Dombrovska, from the Latvian Hunters’ Association has raised major concerns on behalf of the hunting community:

“For many years, our lynx action plan successfully increased the lynx populations and ensured high acceptance of it with basically no conflicts. Through regular monitoring efforts and financial contributions from hunters, the lynx has been the most researched mammal in Latvia. Now, with one unjustified decision all that has been eliminated. Acceptance will decrease, and the number of conflicts will increase, which is bad news for the lynx“.

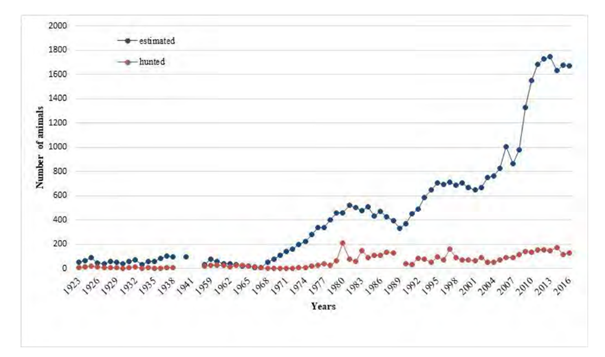

The increasing lynx numbers in Latvia (see Figure 2) with low conflicts prove that the Latvian lynx action plan was one of the most successful large carnivore management systems in Europe. It clearly demonstrates that a management approach supported by key stakeholders (including some regulation by hunting in the case of Latvia) supports conservation targets. FACE therefore calls on policy-makers in Brussels and Latvia to ensure that the successful conservation of lynx prevails and does not fail on bureaucracy – in the best interest of the lynx.

Status of the lynx in Latvia

With around 1600 individuals, the population status of lynx in Latvia is currently the most favourable that it has been in the previous 100 years (see figure 1). It displays increasing population trends and range, while its habitat, future prospects and overall conservation status are favourable. When there was a legal and well-regulated harvest in place, conflicts between the lynx and rural actors such as farmers and hunters were low. At the same time, the social acceptance of the lynx was high and the action plan which permitted hunting was approved by most of the hunting and the non-hunting community.

Figure 1: Population development of lynx in Latvia – including the harvest (source: Action Plan for Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) Conservation and Management)

When strict species protection goes wrong

There are many examples in Europe where the strict protection of species had unexpected or even adverse effects. For instance, in Croatia, before the strict protection of lynx was initiated in 1998, the illegal killing rate accounted for 5%. From 1999 to 2013, illegal killing increased up to 60% of the lynx mortality[2]. Unlike hunting, illegal killing cannot be monitored and regulated and has therefore serious impacts on the natural dynamics of population reproduction, dispersal, the welfare of animals and can lead up to local population extinctions.

[1] Ozoliņš, J., Bagrade, G., Ornicāns, A., Žunna, A., Done, G., Stepanova, A., … & Howlett, S. J. (2017). Action Plan for Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx Conservation and Management 2018-2028. LSFRI Silava, Salaspils, 1-78.

[2] Sindiˇci´c, M.; Gomerˇci´c, T.; Kusak, J.; Slijepˇcevi´c, V.; Huber, Ð.; Frkovi´c, A. Mortality in the Eurasian lynx population in Croatia over the course of 40 years. Mamm. Biol. 2016, 81, 290–294