21 Mar 2020 Is the recovery of wolf in Europe reflected by the latest reports? A success story lost in the data

BACKGROUND – Every six years, the implementation of the EU Habitats Directive has to be reported on by all EU Member States (MS), with particular attention to the conservation status of habitats and species covered by the Directive. During this round of reporting covering the period from 2013 to 2018, all MS were required to submit their reports to the EU by August 2019. These reports are currently being reviewed and assessed by the EU. As part of this process a public consultation on the reports is open until the 8th March 2020.

Based on the reports as submitted by MS, FACE conducted an initial analysis focusing on the conservation status, the population trend, the range trend and the habitat trend of the four large carnivore species in Europe. In general, the individual status assessments of most of the large carnivore populations remained rather constant with some minor deterioration. The situation on wolf populations in the EU is particularly interesting.

WOLF POPULATION, RANGE, AND HABITAT

In the winter of 2018, the first wolf in 100 years returned to Belgium, and completed thereby the animals’ return to all mainland countries in Europe. The wolf is now widely established and reproducing successfully resulting in an exponential population increase. But, is this increase in population size and range also reflected in the outcomes of the species assessments under Article 17? On one hand, yes. Since the first reporting period (2001 – 2006), 20 new wolf populations have been added to the reports. For the 2019 report, in total, 45 wolf populations have been listed under the species assessment. Moreover, the population, habitat and range trend (short-term) of the vast majority of wolf populations is considered positive. Hence, even though, Europe is the continent most affected by human-caused fragmentation, the trend for wolf populations remained rather stable or increased over the years covering the reporting periods. This is largely because the wolf is a habitat generalist.

A MISLEADING IMAGE

However, this largely positive trend is not reflected in the overall conservation status of the biogeographical populations. The conservation status given to a population is of particular importance since it greatly influences the management and conservation of the wolf population.

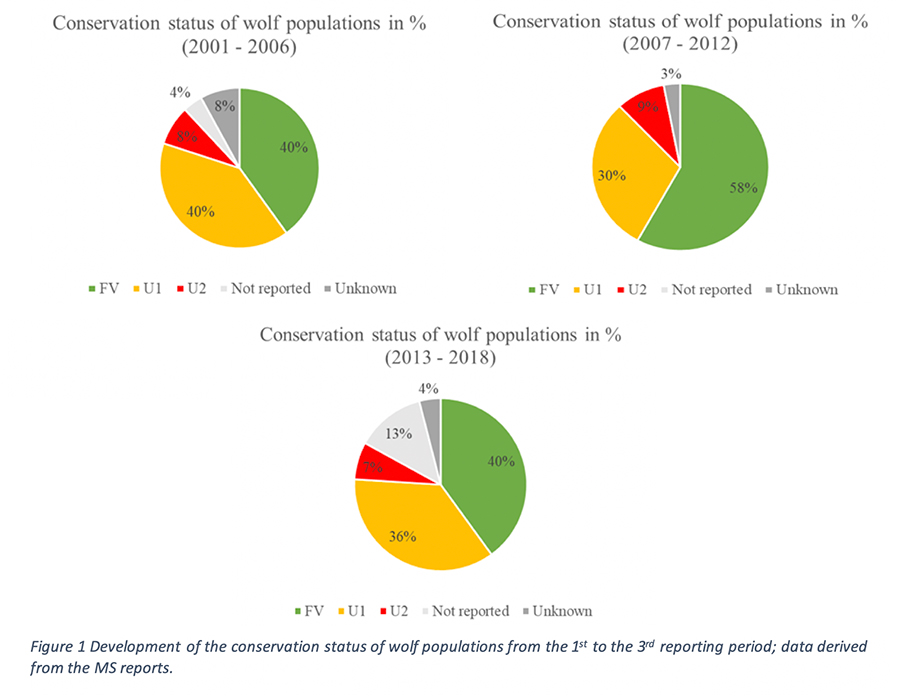

Despite the fact that wolf populations are doing better, for the 2019 report, the wolf populations with a favourable conservation status decreased from 58% (2007 – 2012) to 40%. At the same time, the number of wolf populations with an unfavourable conservation status increased from 39% to 43% (see fig. 1).

So, to answer the question: Is this increase in population size and range also reflected in the outcomes of the species assessments under Article 17? The answer is no; the increase in population size and range of wolves during recent years is not/hardly reflected in the outcomes of the MS species assessments under the Habitats Directive. The main reasons include unknown data, different methods or improved knowledge/more accurate data as reported for some Spanish wolf populations or even highly contested data as in the case of Bulgaria.

Comparing the data of the second and third reports, it is obvious that there is an increase in the population of wolves in Bulgaria. But in its general conclusion, the report nevertheless states that the future prospects of these populations are poor and will even disappear in the coming years. However, the inclusion of newly established populations such as the wolf population of Luxembourg that naturally cannot yet obtain a favourable conservation status, increased the number of populations with an unfavourable conservation status. All of these reasons lead to a misleading impression of the conservation status of Europe’s wolf populations.

Thus, the recovery of wolf populations in Europe is to a great extent unheard and unseen. A success story lost in the data!

DOWNLOAD FULL ARTICLE